Around midnight on Wednesday, August 11th, a group of commodity analysts will gather at a meeting site in the massive South Building of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in Washington, D.C. Once they are assembled, the door will be locked. Cell phones will be collected. Phone and Internet lines will be disconnected. Short of a medical emergency, no one will be permitted to leave before 8:30 am.

USDA produces an estimate of world grain production, consumption, and trade by the 12th of each month. The gathered analysts will consult reports from a worldwide network of agricultural attachés, satellite images of crop vegetation, and the latest weather reports. The widely respected World Agricultural Outlook Board’s report, though little known to the public, is of incalculable value to commodity traders, agribusinesses, and farmers—some of whom stand to gain or lose fortunes on the data it contains.

At 7:00 am on Thursday, shortly after the assembled team has completed its latest monthly estimate of this year’s world grain harvest, a handful of accredited agricultural reporters will be admitted and given access to the data so they can write their stories. At precisely 8:30 am the lockup will end, and phone and Internet lines will be reconnected.

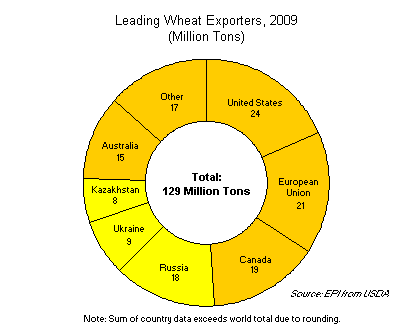

All eyes will be on USDA’s new grain numbers. When the last report was released on July 9th, it showed that the previously estimated 2.2 billion ton world grain harvest had dropped by 18 million tons—a fall of nearly one percent. This month’s report will incorporate the effects of a continuing record heat wave and drought on the grain harvests of Russia, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine, countries that account for one fourth of world wheat exports. The crop losses from the searing temperatures prompted Vladimir Putin’s early August announcement that Russia would ban grain exports at least through December, further raising concerns about the adequacy of this year’s global harvest.

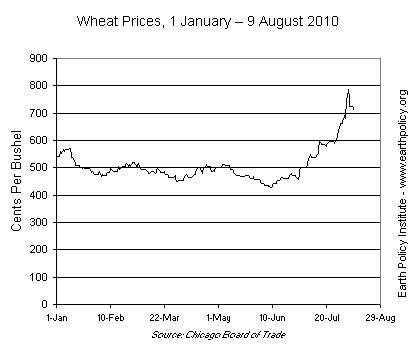

During the two month span between June 9th and August 9th, the world price of wheat jumped by 66 percent. The USDA’s August estimate will show the world harvest shrinking further. But by how much? And how will it affect world grain prices?

Russia’s grain harvest, which was 94 million tons last year, could drop to 65 million tons or even less. West of the Ural Mountains, where most of its grain is grown, Russia is parched beyond belief. An estimated one fifth of its grainland is not worth harvesting. In addition, Ukraine’s harvest could be down 20 percent from last year. And Kazakhstan anticipates a harvest 34 percent below that of 2009. (See data.)

This seven-week crop-withering heat wave is unprecedented for western Russia. July in Moscow was the hottest month in 130 years of recordkeeping. Wildfires are consuming hundreds of thousands of acres of forest, grassland, and ripe wheat fields that have been dried to a crisp in the relentless heat. By early August, hundreds of new fires were breaking out each day. The army was mobilized to assist local fire control units in trying to quell more than 550 fires raging across more than 430,000 acres.

The heat and drought that are shrinking the grain harvest are also reducing grass and hay growth. With less grass for grazing and less hay to carry Russia’s 21 million cattle through the long winter, farmers will have to feed more grain. In late July, Moscow released 3 million tons of grain from government stocks for use by livestock producers and millers. Supplementing hay with grain in cattle rations is costly, but the alternative is to reduce herd size by slaughtering livestock. This would, however, lead to higher milk and meat prices.

Russia and Ukraine together account for nearly half of world exports of barley, a widely used feedgrain in Europe and the Middle East. This year importers will have to look elsewhere. Russia itself could become a grain importer. Indeed, it is hoping to get exportable supplies from Kazakhstan and Belarus, fellow members of a new customs union.

The Russian ban on grain exports and possible restrictions on exports from Ukraine and Kazakhstan could cause panic in food-importing countries, leading to a run on exportable grain supplies. Beyond this year, there could be some drought spillover into next year if there is not enough soil moisture by late August to plant Russia’s new winter wheat crop.

Even as the grain export supply is shrinking, China—essentially self-sufficient in grain for several years—has in recent months turned quietly to Canada and Australia for over half a million tons of wheat from each and to the United States for a million tons of corn. A Chinese consulting firm projects China’s corn imports climbing to 15 million tons in 2015. China’s potential role as an importer could put additional pressure on exportable supplies of grain.

The bottom line indicator of food security is the amount of grain in the bin when the new harvest begins. When world carryover stocks of grain dropped to 62 days of consumption in 2006 and 64 days in 2007, it set the stage for the 2007–08 price run-up. World grain carryover stocks at the end of the current crop year have been estimated at 76 days of consumption, somewhat above the widely recommended 70-day minimum. But how much will carryover stocks drop in the new USDA crop estimate?

No one knows how far grain prices will rise in the months ahead. What we do know, however, is that the prices of wheat, corn, and soybeans are actually somewhat higher in early August 2010 than they were in early August 2007, when the record-breaking 2007–08 run-up in grain prices began. Whether prices will reach the 2008 peak again remains to be seen.

Are this record heat wave and the associated crop shortfall the result of climate change? Not necessarily. No single heat wave, however extreme, can be attributed to global warming. What we can say is that heat and drought similar to that experienced in Russia are projected to occur more frequently as the earth’s temperature continues to rise in the decades ahead. This Russian heat wave lets us see just how brutal future climate change can be.

That intense heat waves shrink harvests is not surprising. The rule of thumb used by crop ecologists is that for each 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature above the optimum we can expect a reduction in grain yields of 10 percent. With global temperature projected to rise by up to 6 degrees Celsius (11 degrees Fahrenheit) during this century, this effect on yields is an obvious matter of concern.

Each year the world demand for grain climbs. Each year the world’s farmers must feed 80 million more people. In addition, some 3 billion people are trying to move up the food chain and consume more grain-intensive livestock products. And this year some 120 million tons of the 415-million-ton U.S. grain harvest will go to ethanol distilleries to produce fuel for cars.

Surging annual growth in grain demand at a time when the earth is heating up, when climate events are becoming more extreme, and when water shortages are spreading makes it difficult for the world’s farmers to keep up. This situation underlines the urgency of cutting carbon emissions quickly—before climate change spins out of control.

Lester R. Brown is the president of the Earth Policy Institute and author of "Plan B 4.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization."

Copyright © 2010 Earth Policy Institute

Etiquetas: Earth Policy Institute, Global Warming, Lester Brown, Russia

0 Comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Suscribirse a Comentarios de la entrada [Atom]

<< Página Principal